This article is part of the Democracy Futures series, a joint global initiative with the Sydney Democracy Network. The project aims to stimulate fresh thinking about the many challenges facing democracies in the 21st century.

Every day, much of humanity now holds in its hands the means to connect and be connected across the world: to family, entertainment and the broadcasts of corporations, states and, increasingly, terrorist organisations such as Islamic State.

This connected world has major implications for social progress and global justice, but so too do the media and information infrastructures on which that world depends.

The project of “networking the world” is more than two centuries old.

While it has always been the project of states, it has increasingly become the preserve of some of the world’s largest corporations including Facebook, Google and, less well known in the West, China’s Tencent and Baidu.

Profit, freedom and inequality

Just as economic models rooted in markets and consumption are expanding into ever more world regions and intruding into ever more domains of everyday life, so corporate logics are colonising media and digital platforms.

Take education as one example: concerns are developing regarding school learning materials increasingly provided not by the state but by commercial media companies such as Apple and Google.

More recently, Facebook faced civil society opposition in India when it sought to introduce its Free Basics platform as a default means of internet access for less affluent populations.

However, the same move has gone unopposed in African countries facing greater resource challenges.

Market forces have appropriated the design, regulation and pricing of the platforms we use to connect, portray the world around us, express our political allegiances and even forge our visions for the future (as explored, for instance, in tech evangelist Kevin Kelly’s work).

Profound inequalities

Particularly in the Global North but also the Global South, the information networks and communication protocols that underlie media infrastructures are designed and operated by private, corporate entities.

Direct technical authority over networks and protocols gives these entities an authority that is inherently regulatory.

Global platform companies such as Google, Twitter, Facebook, Microsoft and Apple – each of which occupies a dominant market position globally – enjoy correspondingly stronger and more pervasive regulatory power. Yet these platforms have so far been driven by only one goal: profit.

The story of expanding global media networks is often told as if they spread freedom everywhere, liberally and evenly. But when we ask freedom for whom, the tale gets more complex.

There are profound inequalities in basic media access within nations and among continents. While global elites may be better connected everywhere, the same is not true of those who work for them. Media systems offer tremendous communication resources to people who can function in Western languages, are able-bodied and have the necessary buying power.

Unfortunately, in Colombia, a home internet connection costs 20% (US$48) of the minimum wage (US$217/month), putting it out of reach for a domestic worker.

Justina, a full-time domestic worker in the city of Barranquilla, told us in a recent interview that she must instead buy a $1 Tigo prepaid card at the corner store that gives her access to precarious internet for only 48 hours at at time.

The inequalities are even greater in media production. Even if a smartphone gives migrants an image of the country they hope to reach, they will most likely lack the ability to influence how their arrival will be represented.

Our media representations of the world’s problems are drawn from a very narrow pool of perspectives. Subsequently, our media systems showcase certain voices while marginalising others, especially people of colour, differently abled people, migrants, women and girls.

From Hollywood, where 96.6% of all directors are male and only 7% of films are racially balanced, to digital platforms where elites find new ways to gain a following, the media shows us a world as lived only by a few. The public conversation about access needs to consider how opportunities for content creation and visibility can be shared more widely.

It is a myth that rural communities, Indigenous people and the Global South are not interested in media and the digital world, but sadly our current media infrastructures carry little – if any – input from these large sections of humanity.

What if media infrastructure and digital platforms were designed with communities’ diverse languages, needs and resources in mind?

The results have the potential to be transformative, as when the Talea de Castro Indigenous community in southern Mexico designedRhizomatica Administration Interface (RAI), a graphic interface for a local cellphone network responsive to local information needs, languages and modes of communication.

Much more often, however, the algorithmic mechanisms that shape what is available to users of digital platforms are driven exclusively by an advertising logic that undermines diversity and reproduces the social capital of those with power.

Two principles for reform

Media and information regulation shows a more subtle, but equally powerful inequality. National and multinational regulatory bodies from the mass media era are struggling to adapt in the age of smartphones and tablets.

Content delivery’s increasing shift to mobile devices gives corporations, not states, the dominant influence over what can be watched, when and by whom. Consequently, it is corporations, not regulators, that now set the parameters of what can be received on what device, and by what means.

The problem is that the regulation of media and digital platforms is too important to cede to a few powerful organisations that make decisions, implement policy and design online architectures behind closed doors. Instead, transparency and greater civic participation should be the guiding principles of internet governance, policy and regulatory frameworks.

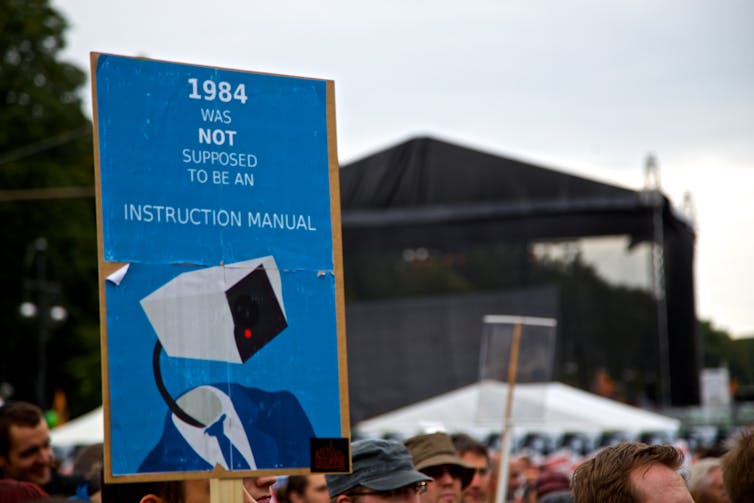

Crucial to this is the internet’s capacity for surveillance – not just when we buy goods and services online, but also in ordinary social interaction.

The increasing dependence of all communication flows gives corporate networks the ability to use and reuse the resulting data to make algorithmic discriminations between consumers and citizens.

In many parts of the world and for large parts of the population, everyday life routinely involves online access to a wide variety of purveyors of news, information and popular culture, as well as search engines, social networking platforms and other content aggregators that seek to help users find, organise and make sense of it all.

While access to these resources may be offered at no financial cost to users on an advertiser-supported basis, consumers often pay a price in the form of the automated collection of information about their personal reading, viewing and listening habits. This information can be used for surveillance and censorship, or to target advertising and suggest content more likely to appeal to each user.

Such surveillance has so far been largely beyond public regulation, yet this new ability to deeply modulate how the social world appears to us has not escaped national governments’ notice, for example in China, India and the United States.

It is undeniable that the media’s rapidly changing infrastructure offers huge opportunities for those campaigning for social progress to connect, act and challenge the significant inequalities that underlie media systems themselves.

We propose two principles to guide this expanding struggle.

The first is that media cannot effectively contribute to social progress until opportunities for access and participation in the production and development of media content are more widely shared. The second is that media infrastructure is a common good whose governance and design should be much more open to democratic engagement than currently.

Ignore these principles, and the world’s visions of social progress will be less effective and far less diverse. Start to take these principles seriously, and the global struggle for social justice becomes both deeper and more open to the hopes of populations long ignored.

The authors are coordinating lead authors of Chapter 13 of the International Panel for Social Progress’s draft report. Public comments are welcome here.

Creative Commons License

Fonte: https://theconversation.com/why-the-media-is-a-key-dimension-of-global-inequality-69084